This is from the NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY MUSEUM & LIBRARY BLOG about the following post we authored:

“I Approve This Message,” an exhibition about the emotional impact of political advertising in a landscape altered by the internet, was set to open at the New-York Historical Society this September. The COVID-19 lockdown halted those plans, but we want to share a few of the exhibition’s themes, particularly as we barrel towards our new date with destiny on election day, Nov. 3. Here we look at the fast developing world of digital campaigning and how to become a more aware consumer of online content and social media as we approach Election Day 2020. photo: Alessio Jacona Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg

“Opposition Growing” … “Responses Needed” … “Critical Match” … “HUGE news” …

It’s likely you’ve been inundated with emails supporting 2020 election candidates. Some, you may have contributed time or money to; others, you don’t even recognize. It’s a little like shopping on your favorite site on Wednesday and seeing a related ad on a different site on Thursday.

What you’re witnessing are political pros using the same marketing techniques and powerful technological tools their commercial counterparts have successfully used for decades. The difference is that commercial advertising has truth-in-advertising laws to govern their messages, while online political ads go completely unregulated.

Here’s why you should care…

On any given day, your privacy is being compromised by internet and mobile phone technologies. You are being tracked by advertisers, whether you’re watching TV at home, cheering at a rally, buying a campaign hat, visiting a favorite website, or reading a news story on your phone.

At least 70 different tracking technologies are used to capture your actions, like when you open your email.”

—Dec 2017 Wired article by Brian Merchant; Tactical Tech study

There can be literally thousands of data points specifically about you, many available from third party sources that have the ability to integrate with an advertiser’s or political campaign’s own database.

What is all of this data for? It’s in the service of microtargeting: identifying your interests and making assumptions about who you are and what you like—the friends you have; the books, groceries, or shoes you buy; where you’ve dined or gone to church, synagogue, or mosque; who you’ve voted for; what events you’ve attended. If you are biased or irrational, hopeful or angry, it is all noted. Because once an algorithm gets to know you, a message—whether true or not—can be tested and targeted specifically to your liking. Your confirmation bias can be reinforced.

Microtargeting transforms the public square of politics into the psychological mugging of every voter.”

—Roger McNamee, author, Zucked: Waking Up to the Facebook Catastrophe

Facebook is a pro at this, and Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign famously—and aggressively—used it to his advantage. The ads you received on Facebook from the Trump campaign were tested, tested, and tested to come up with just the right mix of creative elements and messaging in order to attract you to open, read, follow, contribute, sign-up, like, or share with others.

Most of the Trump campaign’s digital ad budget went to Facebook, testing more than 50,000 ad variations each day.[i]

—Brad Pascale, Trump Digital Director, on 60 minutes as reported by The Guardian

According to Facebook Vice President Andrew “Boz” Bosworth in a CNBC story: “[Trump] ran the single best digital ad campaign I’ve ever seen from any advertiser” (in other words, better than even the product marketers.)

For campaigns, it’s obvious how beneficial all of this can be: Increased engagement delivers email addresses, donations, event attendance, likes and dislikes, contact names, and other actions that help build word-of-mouth, excite the base, broaden support and, ultimately, win your vote. But for the general public, there is little to no protection from bad actors who move beyond aggressive messaging and into outright deception, fakes, and fraud. This can be nefarious and, even, destructive.

For the moment, microtargeting in the U.S. is here to stay and difficult to avoid if you have any kind of life online. The challenge is to be conscious of the ways we’re being targeted so that we can protect ourselves.

With just a modicum of knowledge and effort, it’s not that difficult to pick up on some of the ploys. Here are seven of the more common to be on the lookout for this election season:

1) REDIRECTS AND COPYCAT WEBSITES

You can be unknowingly “redirected” from a trusted website you are looking for to a different site full of alternate information. For example, early in the campaign a parody site named “Joe Biden for President 2020″got more traffic than his official one. Another parody site, trumphotels.org, went viral, getting more than a million visitors. Since COVID-19 appeared, illegitimate websites have sprung up that purport to sell difficult to get items like PPE, toilet paper and hand sanitizer. They nab your information, but don’t send you a purchased product.

What You Can Do: First, alert everyone in your family—especially your children—to the malicious ways a site can trick them. If you are contributing to a candidate or buying a product—basically whenever you use a credit card—be sure the HTTP on the url (website address) has an “s” at the end, which means the site is secure.

A screenshot from the fake website trumphotels.org

2) FAKE VIDEO

These videos seem to be real but have been digitally manipulated in ways that can be obvious or subtle. The recent example that purported to show Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi slurring her words is an example of what some call a “cheap-fake.” More sophisticated and frightening versions—described as deep fakes—are far more difficult to decipher and are waiting in the wings.

What You Can Do: If a video seems too good (or too bad) to be true, you may want to check on its legitimacy. Look for tell-tale signs: the eye gaze is wrong or the eyes don’t blink; the hair or teeth look synthetic; the lip syncing is off; the skin tone is blotchy; there’s blurriness where neck meets the head; there are missing shadows. Also, judge the credibility of the speech: Would you expect this person to say that? If you have doubts, most factchecking sites like politfact.com or snopes.com follow wide-spread ruses and report on them.

3) DECEPTIVE CAMPAIGN ADS FROM FAKE SOURCES

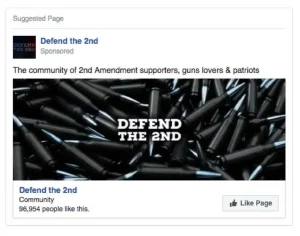

Misleading campaign ads are designed to move far and fast and sow confusion online. During the 2016 presidential election, there was a concerted, coordinated campaign by the Russian-backed Internet Research Agency to create hostility, divide Americans, and discourage people from voting. Largely undetected at the time, some 3500+ divisive Facebook ads were microtargeted to U.S. voters on topics ranging from immigration, radical Islam, gun rights, and injustice against Black Americans to name a few. Facebook recently announced it will block advertising from state media, but you can’t just count on someone else.

What You Can Do: Many of these ads had misspellings or grammatical errors, so if you were paying attention, those would have been a red flag. Many also identified themselves as coming from nonexistent organizations and websites that had similar names to real ones. If you start seeing new divisive ads or receiving something digitally that you never have seen before, be sure and check whether or not the sender is legitimate.

A screenshot of a social media ad from a fake organization that was meant to appeal to and anger gun right supporters in 2016.

A screenshot of a social media ad from a fake organization that was meant to appeal to and anger gun right supporters in 2016.4) FAKE SOCIAL MEDIA ACCOUNTS

These are social media accounts that mimic real people or entities and do things like amplify existing content online or start unfounded, but difficult to disprove, rumors. A subset of these are bots, automated computer code that appears human and only exists to exaggerate the prevalence of a certain point-of-view or choke off organic debate. A number of social media companies have instituted new practices to protect users, but accounts are so numerous, it’s doubtful they can all be caught.

What You Can Do: Pretty much the same things you do for fake campaign content above—check out the sender. As for bots, it’s not easy to tell if you’re interacting with one, but there are nuances that raise red flags.

5) TROLLING

If you’ve spent time on Twitter or on any comment section, you’ve encountered a troll who seems intent on picking a fight no matter what the subject matter is. They’re all about stirring up trouble and eliciting knee-jerk reaction from unsuspecting readers.

What You Can Do: If you ever read comments online, you can easily pick up on this phenomenon. And then you can proceed to do the only thing that disarms a troll: ignore and move on.

6) SPEAR PHISHING

This con involves malicious emails ostensibly sent from a trusted sender that gets targets to reveal confidential info. (If you’re a high profile hot-shot, it’s called whale phishing.) For example, maybe you contributed to a candidate you trust and you received an email, seemingly from the same source, asking for additional, confidential information or providing a link to a login page. If you comply with either request, it makes it easy for a scammer to harvest your credentials for their own purposes.

What You Can Do: Check, check, check the sender and the url of the webpage before you click.

7). HACKS AND LEAKS

Remember the Wikileaks release of hacked emails from Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign? Suffice it to say, hacks and leaks can have a huge impact on elections, changing hearts and minds and impacting enthusiasm and outcomes.

What You Can Do: Everyone wants to be in on a secret, particularly when it’s headline news. But at the very least, the next time any campaign or entity is hacked, don’t just react. Ask yourself: Who is benefitting? Is there another side? And then decide: Should I change my support based on this information?

The bottom line for surviving the election season: Be aware and be suspicious. Always check the url before you click, and look for content with obvious and subtle distortions. If something just doesn’t feel right, check if anyone has reported on a similar experience. If you don’t believe the reporters and fact-checkers? Verify by digging up the information on your own.

Don’t just accept what you receive, read, and hear on the internet. Don’t just react and click or share quickly. Recognizing that miscreants are dining on your data and serving it up to others on a platter for their use can help you avoid spreading their misinformation.

Read More: “I Approve This Message”: The Birth of TV Campaign Ads and 9 Presidential Election Classics

Read More: Did “I Approve This Message” Live Up to its Promise?

Written by Harriett Levin Balkind, Founder of nonpartisan HonestAds.org and creator and guest curator of the I APPROVE THIS MESSAGE: Decoding Political Ads exhibition hosted by the Toledo Museum of Art, 2016

EXHIBITION EXPLORES HOW YOUR HEART — NOT YOUR HEAD — IS IMPACTED BY POLITICAL ADS

EXHIBITION EXPLORES HOW YOUR HEART — NOT YOUR HEAD — IS IMPACTED BY POLITICAL ADS